When I was a kid, I used to read the encyclopedia. Rather than attempting to identify myself with the characters of more typical teenage narratives (or, at least, let’s be honest, narratives by adults about teenagers. Which is what “young adult fiction” ultimately is), I habitually spent my quiet reading hours with the volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica (an early 1980’s set in black pleather) and a rather brightly colored set of Funk and Wagnall’s Wildlife Encyclopedias. To this day, I credit the latter with my ability to identify, by sight, a hoopoe, an okapi, at least seven types of foxes, and nearly all members of the family Paradisaeidae (order Passeriformes). More than a decade before the internet, and even longer before the advent of Wikipedia, I was happily wiling away the hours with entries detailing everything from the early modern scientific revolution, to Medieval calligraphy, to dry commentaries on Isaac Newton’s 1687 Principia. Now, I don’t mention this to imply, in any sense, that reading an encyclopedia as a ten-year-old makes you smarter or more academically inclined (though I am sure it helped along the way somewhere), I mention it here because this is the earliest memories I have of being excited by a world full of Great Big Things.

Bug collecting and fossil collecting are part of seeing the world in this way; constructing one’s own Cabinet of Curiosities in order to categorize and make sense of a world that is complex, fascinating, and wholly beyond one’s limited experiences. But here it is that anthropology challenges us further, amid the desperate urge to classify and harmonize everything into orderly taxonomies; to see our categories, not as a kind of access to direct truths but as a kind of mythology in its own right. This isn’t to suggest, of course, that scientific classification is mere fable or fantasy, or that it isn’t useful in helping us to explain and predict natural processes, but that the choice to associate certain qualities over others or to group certain characteristics and strata for one reason over another comes with its own kind of partiality.

My thinking along these lines echoes the commentaries of British paleontologist Richard Fortey, who once remarked that “like pebbles on the beach of Hinlopenstretet, history, too, is a succession of endless details, and there is an infinite choice whether to pick this one or that (Life, 1997: 24).” Or more specifically, in this case, that “the history of life is filtered by the very processes that preserve it (18).” It is not accidentally that I choose to quote Fortey here, who, as a paleontologist fascinated by the earliest fossils of Precambrian and Cambrian life, also goes on at length to question how things are classified, how one type of creature becomes associated with another, and how such early taxonomies of space and time form their own kinds of “mythological units.” As an anthropologist who works primarily with Shaligram Stones, it is this issue of classification that weighs most heavily on my work at present.

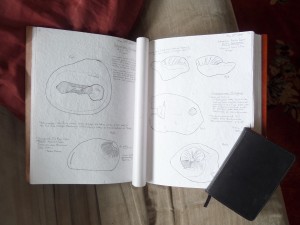

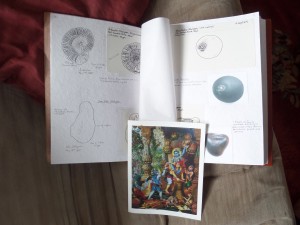

In the discourse of science, Shaligram Stones are black shale fossil ammonites from the Early Oxfordian to the Late Tithonian age near the end of the Jurassic period some 165-140 million years ago (Geological Survey of India 1904: 46). In the discourse of Hinduism, Shaligram Stones are the direct, aniconic, manifestations of Vishnu, gifted to the sacred Kali-Gandaki River (or “cursed” to appear in the river, depending on which origin story you follow) as objects of veneration for worthy devotees. In terms of classification, both are “true” in that both sets of classification tell us something about the world these objects inhabit. In one sense, these fossils tell the story of a Himalayan region once covered by a shallow sea long before the shifting of tectonic plates pushed ragged peaks into the clouds. Before mammals had arrived on the scene, before humanity was even so much as a teleological consideration. In another sense, these sacred stones tell the story of human mobility and meaning-making, of the making of persons and cultures across time and space. They tell a story of a time of divine intervention, the musings of gods, and the creation of the world also long before humanity had much say in the way of things. The famous geologist’s metaphor is to describe the careful peeling back of stratigraphic layers of rock as reading the pages of a book. But what Shaligram Stones show us is that we are not so much “reading” this story, as equally as we are “writing” it.

All narratives require a scale. All stories need a chronology. And for this reason, like it or not, human motivations will always creep into descriptions of the natural world just as much as they dominate our understandings of ritual and religion, of ethnicity, race, and nation. These stories are paradoxical and difficult. The further we delve into the world around us, the more obscure are the events and the less certain the narrative. But we must start somewhere, and in a world of Great Big Things, let it begin with the thing itself (as Appadurai would say). If nothing else but to gain a new appreciation for the richness of life and our human place within it, where a fossil can be a deity and a deity can be a fossil, both millions of years old and imminently present, and have logic be all the better for it.