Whenever I am paging through endless spreadsheets of museum collection data on fossils I am always on the lookout for a few magic words: Ammonite, Spiti Shales, Nepal (or Tibet), Himalayas, and possibly Perisphinctes. Recently, while reviewing some fossil collection data supplied by the Oxford Museum of Natural History in the UK, I can across just such a listing for a series of Himalayan ammonite specimens they had listed as purchased at a bazaar in Southern Tibet.

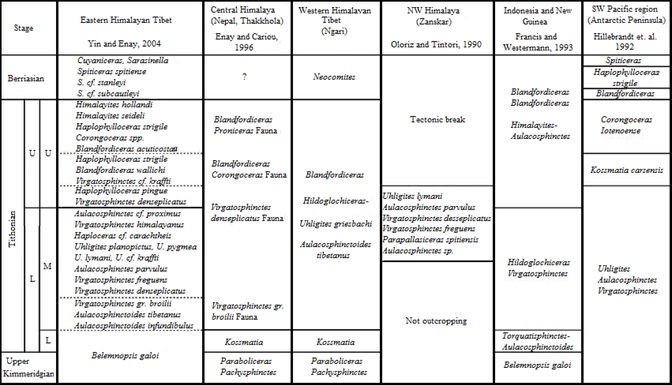

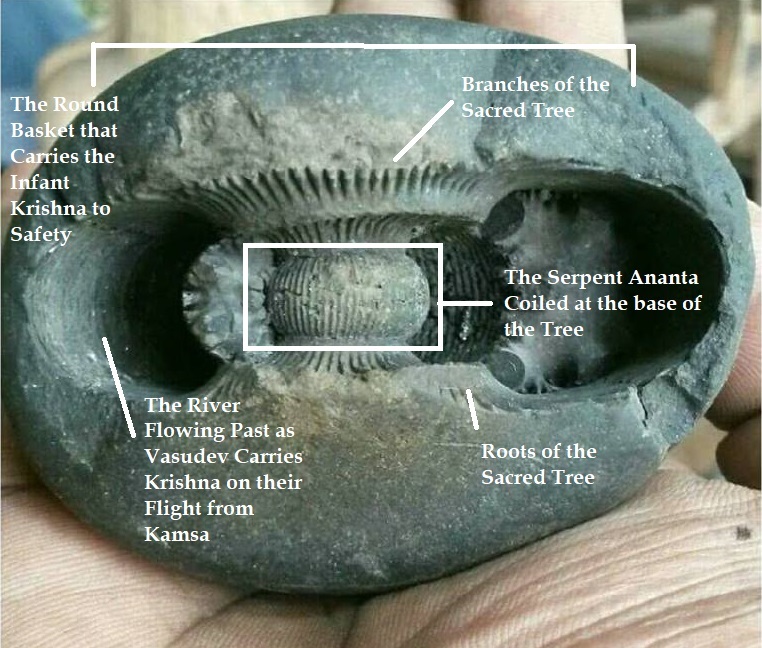

While my current review of worldwide museum collections is geared towards an upcoming second manuscript on Shaligram interpretive traditions, it did also get me thinking about labels again. The vast majority of the Western world knows Shaligrams only by scientific categories and because of this, is largely ignorant of their meanings beyond that of a common index fossil (more suited to the backroom of a collection or to a souvenir shelf than much else). They are fossil ammonites, they are primarily found in Nepal and Tibet, they are produced by a geological formation known as the Spiti Shales, and they are comprised of roughly four species of extinct Jurassic shellfish: Blandifordiceras, Haplophylloceras, and Perisphinctids (including both Aulacosphinctus of the Upper Kimmeridgian/Lower Tithonian and Aulacosphinctoides of the Upper Tithonian). Other Shaligram formations include belemnites (such as the Ram Shaligram) and the bivalve Retroceramus (such as the Anirudda Shaligram) but for the most part, classic Shaligram manifestations are, by and large, comprised of various black shale ammonites that fit the aforementioned paleontological criteria. In other words, these categories have produced a specific kind of knowing about Shaligrams and about fossils in general that represents a particular perspective in the history of scientific knowledge production.

In Ancient Greece, ammonites were known as Cormu Ammonis, Corni de Ammone, or Cornamone because their shapes were thought to resemble the tightly coiled ram’s horns used to represent the Egyptian god Ammon. Pliny the Elder (AD 23 – AD 79) even referred to them in the 37th volume of his work Naturalis Historia. In it, he writes: The Hammonis cornu is among the holiest gems of Ethiopia, it is golden in colour and shows the shape of a ram’s horn; one assures that it causes fortune-telling dreams (see also Nelson 1968). The golden colour he refers to is a likely reference to the fact that many ammonite fossils, including Shaligrams, are often covered in iron pyrites which give them a sparkling golden appearance. Georgius Agricola, sometimes referred to as the father of mineralogy and the author of De Re Metallica, a work based on Pliny’s Naturalis Historia, also referred to ammonites as Ammonis Cornu. Even today, ammonite genus names often end with –ceras, the Greek word for “horn.”

The Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner also included some ammonite illustrations is his work De rerum fossilium (1565), but even toward the end of the 17th century, it is especially interesting to note that the organic nature of ammonites remained under debate (a debate which takes places in the Hindu Scriptures as well most notably in reference to the formative workings of the vajra kita, or the thunderbolt worm).Robert Hooke, the famed experimental scientist and nemesis of Sir Isaac Newton, was fascinated by the logarithmic coil of ammonite shells and their regularly arranged septa (recall the classic image of the golden ratio). It was he who reached the conclusion that ammonites were not only of organic origin but also widely resembled the nautilus and may therefore be related. However, it wasn’t until 1716 that ammonites would finally join scientific taxonomy with a classification scheme first recorded by another Swiss naturalist, Johann Jacob Scheuchzer. The modern form of the word ammonite was then coined by the French zoologist Jean Guillaume Bruguire in 1790, but it wasn’t until 1884 that the subclass Ammonoidea was finally formalized in modern zoological taxonomy (Romano 2014).

In China, however, ammonites were called horn stones (jiao-shih) and were typically used in traditional medicine. Japanese texts, on the other hand, refer to them as chrysanthemum stones (kiku-ishi) and Buddhists interpreted their clockwise spirals (a representation of the direction in which the universe rotates) as a focus for meditation or as symbols of the eight-spoked wheel of dharma (an interpretation currently shared by many Buddhist pilgrims to Mustang, Nepal as well). Additionally, among ancient Celts, these fossils have been interpreted as a kind of petrified venomous snake (ophites) and referred to as serpent stones. In medieval England, ammonites (along with various other types of fossils) were taken as evidence for the actions of Biblical saints such St. Patrick, St. Keyne Wyry of Wiltshire (ca 461 – 505), or St. Hilda of Whitby (ca 614 – 680). According to Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion,[i] fossil ammonites were serpents that infested the region of Whitby before the coming of St. Hilda, who subsequently defeated the serpents and turned them to stone on the site where she intended to build an abbey (see also Skeat 1912).[ii]

In the Americas, Cretaceous baclitid ammonites were also once collected by the Indigenous peoples as buffalo stones and were kept in medicine pouches as aids in corralling bison (Mayor 2005). Called Iniskim, members of the Blackfoot First Nations continue to harvest bright opalescent ammonites for ceremonial purposes even today.[iii] Furthermore, aside from their role as Shaligrams, ammonites also have a long and storied history more broadly in what Alexandra van der Geer refers to as the “fossil folklore” of South Asia. She relates in detail, for example, entire regions of fossil beds containing not only ammonites but ancient giraffes, elephants, and tortoises near the Siwalik Hills of the Himalayas in India, which are used as evidence in proof of the great cosmic battle of Kurukshetra as described in the Mahabharata epic and which are also visited by religious pilgrims from all over the world (2008).

Isn’t it surprising then, given the incredible history of ammonites beyond geologic categories, that this information, these labels, almost never make it into museum collections? I’ve never seen, for example, any such exhibit that displays fossils in this way, unless, of course, we start talking about religious museums. I have no doubt that the Creation Museum in Kentucky has its own take on the fossil record and one that, undoubtedly, stands in opposition to science; that makes claims to truth over evidence and only that which aligns with their particular interpretation of Biblical texts. But like so many Shaligram practitioners, I do not mean to present Shaligrams here as any kind of potential foil to scientific inquiry or to imply, in any way, that the creation stories of Shaligrams are distinctly at odds with evolutionary theory. Because, for the most part, they aren’t (see: “Living Fossils” – https://thefamiliarstrange.com/2018/06/07/living-fossils/). And, in fact, I might argue that this division of modern museums and their preferred display narratives is more representative of the politics of religion and science in the West broadly than it is about what a Shaligram, or even an ammonite really is.

What I imagine then is the opportunity to design a museum exhibit that pays tribute to all kinds of ways of knowing; to blend the narratives of Deep Geological Time with Mythic Time in such a way as to demonstrate the richness of fossil traditions both within science and without. I’m not entirely sure what I think it would look like just yet but if I were to incorporate Shaligrams, I would be sure to present them respectful to the contexts of their ritual practices, to emblazon placards with instructions on their interpretive traditions (I can see it now: How to Read a Shaligram! In Six Easy Steps), and to link the geological understanding of the tectonic creation of the Himalayas with the stories of sinmo and asuras (demons), Vishnu and Shiva, and the transformation of the goddess Tulsi into the river Gandaki. I would strive to introduce museum goers to the stories of gods and monsters, tectonic plates and dinosaurs, evolution and creation through labels, exhibits, and collection data that are all-at-once scientific, spiritual, and imaginative. And, if nothing else, to preserve all manner of histories; from those told by the ancient peoples who first encountered fossil stones, to the faithful pilgrims who continue the tradition, to the scientists who interpret them now, to the stories told by the stones themselves. After all, what is the Past if not the simmering cauldron from which the present emerges?

—

[i] Lovett, Edward (September 1905). “The Whitby Snake-Ammonite Myth.” Folk-Lore. 16 (3): 333“4.

[ii] Skeat, W.W., 1912. Snakestones and stone thunderbolts as subjects for systematic investigation. Folk-lore, 23: 45-80. Additionally, during the 19th century, it was not uncommon for people to carve images of snake’s heads around the bottom aperture of the ammonite shell so as to better the appearance of a snake in coiled repose.

[iii] See also: Rainbow Ammonites and Bison Stones available at https://albertashistoricplaces.wordpress.com/2018/01/10/rainbow-fossils-and-bison-calling/

Further Reading:

Etter, W. 2015. Early Ideas about Fossil Cephalopods. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology 134:177-186.

Monks, N. and P. Palmer. 2002. Ammonites. Natural History Museum, London, London, England.

Mychaluk, K. A., A. A. Levinson, and R. L. Hall. 2001. Ammolite: Iridescent Fossilized Ammonite from Southern Alberta, Canada. Gems & Gemology 37: 4-25.

Peck, T. R. 2002. Archaeological Recovered Ammonites: Evidence for Long-Term Continuity in Nitsitapii Ritual. Plains Anthropologist 47:147-164.

Reeves, B. O. K. 1993. Iniskim: A Sacred Nisitapii Religious Tradition. In Kunaitupii: Coming Together on Native Sacred Sites, Their Sacredness, Conservation, and Interpretation, edited by B. O. K. Reeves and M. A. Kennedy, pp. 194-259.